The unmaking of the monarchy

Why we may run out of royals

A bas les princes! Last week the New Statesman published a cover piece by its deputy editor calling for the abolition of the monarchy. Such pieces in mainstream magazines - even of the centre left – have been rare indeed. With the briefest of interludes in the middle of Victoria’s reign the cause of republicanism has for several centuries been seen as the province of the kind of corduroyed eccentrics who might otherwise have taken up Esperanto or one world government. And of Polly Toynbee. So was this major article a harbinger of a new trend?

On video the author, Will Lloyd, explained why he had now joined the Republican movement. He explained that he had always considered himself to be a low-level monarchist (ie no Jubilee mugs but also no desire to champion a lost crusade) until he read Andrew Lownie’s recent book on the Yorks – which I wrote about on here a few weeks ago.

Lloyd explained that it was one specific passage that had led to him losing his culottes. This was where Lownie told the story of how, at dinner one evening, the then Prince Andrew (last week reduced in the ranks to Mr A. Mountbatten-Windsor) had played a prank on a woman guest, which ended up with him pushing her face into a plate of paté. That one moment, said Lloyd, had converted him to the need for an elected head of state.

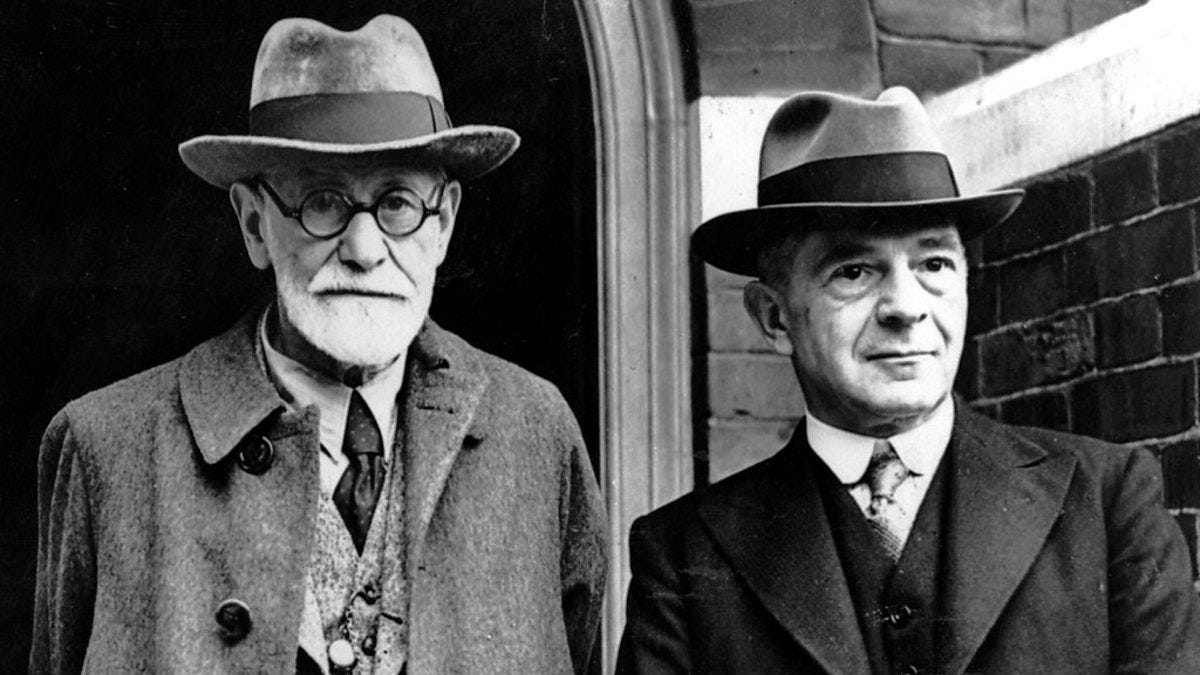

A Freudian view of the King

Previous contributors to the magazine might have regarded this conversion as a touch capricious. In January 1936, Ernest Jones – the foremost British disciple of the still-extant Sigmund Freud – wrote a lengthy piece for the magazine entitledThe Psychology of Constitutional Monarchy explaining why the institution so perfectly fitted the collective unconscious needs of the British people.

The essay was written in the immediate wake of the death of George V and weeks before his heir’s love affair with the American divorcee Wallis Simpson developed into a full-blown crisis. At the time Jones would have been contemplating a Europe of extremes in which Hitler, Mussolini and Stalin ruled over half the territory, republican France and Spain were beset by civil strife, Austria was run by clerical fascists, Greece, Hungary and Portugal by parafascist dictatorships, and Poland by authoritarian nationalists. In these circumstances even a left liberal like Jones could see that Britain domestically (he didn’t deal with the colonies) seemed happier with its constitutional settlement.

Jones began his argument with Freud’s observation about the fundamental contradiction – the ur-battle – inside the developing human psychology: that the “dichotomy of man’s nature expresses itself most vividly in the child’s relation to his parents – the famous Oedipus complex…”

On the one hand, Jones explained, the child wants and needs the guidance of the parent to control his or her own impulses; but if that control is felt to be oppressive, she will rebel and “clamour for freedom”. As with fathers, so with kings, since both perform a similar function. “No psychoanalyst”, wrote Jones, “would hesitate, on coming across the person of a ruler in a dream, to translate ruler as father, and he would at once be interested in the way in which the subject’s conscious attitude towards the ruler was being influenced by his underlying attitude towards his father”.

Such a situation is fraught with violent possibilities and – scaled up to nations –revolutionary potential. But with constitutional monarchy, “the essential purpose of the device is to prevent the murderous potentialities in the son-father (ie governed—governing) relation from ever coming to too grim and fierce an expression.” As it seemed to be doing everywhere else.

Jones then departed from psychoanalysis and – as monarchists usually do - became metaphysical. Monarchy itself, he argued, has a deep purchase on the imaginations of human beings, a “mysterious identification of king and people [which] goes very far indeed and reaches deep into the unconscious mythology that lies behind all these complex relationships.”

As if anticipating the criticism likely to come his way from the more radical readers of the New Statesman, Jones got his retaliation in first. “When the sophisticated pass cynical comments on the remarkable interest that majority of people take in the minute doings of royalty and still more in the cardinal events of their births, loves and deaths,” Jones pronounced, “they are often merely denying and repudiating a hidden part of their own nature rather than giving evidence of having understood and transcended it.”

In Jones’s formulation, “the sophisticated” are battling their own real desires which are obscured by their own veneer of intellectual abstraction. The “unsophisticated”, in being fascinated by the minutiae of royal lives, are in fact in touch with their needs – if unaware, of course, of their own motivations. Anyway, the result is a kind of contentment. It was an assessment with which even George Orwell agreed. And for my entire lifetime this phlegmatic assessment or something like it, has guided elite attitudes towards the monarchy.

The opium of the people

“This nation will never be so well contented, never thoroughly happy, without a king.” The last words before execution of James Stanley, Earl of Derby, 1651

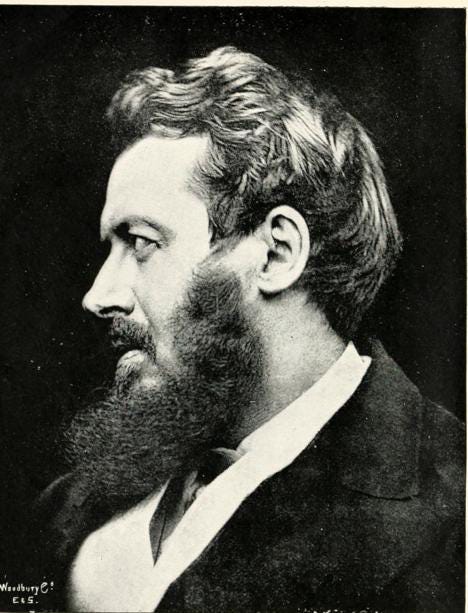

There was also a more cynical version of Jones’ thesis, which you might think of as saying the quiet bit out loud. The great Victorian public intellectual and author of The English (sic) Constitution, Walter Bagehot, became the ubiquitous go-to authority on how the British state was constructed. The founder of The Economist, friend to the stars of his time, cited on 125 occasions in Gladstone’s diaries, Bagehot was writing

as Queen Victoria approached the thirtieth year of her reign and hadn’t yet managed a transition from wholly withdrawn and unpopular widow to mother of the nation.

He was also writing towards the end of the long gap between the Great Reform Act of 1832 and Disraeli’s expansion of the franchise in 1867; an extension which would still allow only one third of the adult male population to vote - so his audience was not the factory workers of Manchester or labourers of Norfolk.

Bagehot set out to explain to the educated classes the value of Britain’s constitutional monarchy and to show why it was that ordinary people required such an obviously undemocratic institution. The monarchy, he concluded…

…acts as a DISGUISE. It enables our real rulers to change without heedless people knowing it. The masses of Englishmen are not fit for an elective government; if they knew how near they were to it, they would be surprised, and almost tremble.

Bagehot’s view was that monarchy was essential because it was comprehensible even (and perhaps especially) to the stupid.

We have no slaves to keep down by special terrors and independent legislation. But we have whole classes unable to comprehend the idea of a constitution – unable to feel the least attachment to impersonal laws. Most do indeed vaguely know that there are some other institutions besides the Queen, and some rules by which she governs. But a vast number like their minds to dwell more upon her than upon anything else, and therefore she is inestimable.

According to Bagehot, the personification of rule allows an identification that is impossible in a Republic. Like Jones he looked across to the continent with complacency and with the American Civil War just concluded, there seemed no lessons to be learned from the divided republican United States. Also there were the ladies to be considered. They might not have the vote but there were an awful lot of them…

No feeling could seem more childish than the enthusiasm of the English at the marriage of the Prince of Wales, but no feeling could be more like common human nature as it is, and as it is likely to be. The women – one half (of) the human race at least – care fifty times more for a marriage than a ministry. A princely marriage… rivets mankind.

Such pageantry was a useful diversion, introducing “irrelevant facts into the business of government, but facts which speak to ‘men’s bosoms’ and employ their thoughts”. Otherwise, Bagehot implied, these might be employed elsewhere and to worse effect. Wilde’s Lady Bracknell could hardly have put it better. In Britain religion was not the opium of the people – the monarchy was.

Bagehot, though, was clear that the constitutional monarchy must stand apart from any hint of partisan politics. So he added this warning, which included a phrase that is trotted out, shorn of context, whenever the modern monarchy is discussed in broadsheet newspapers:

The monarchy’s mystery is its life. We must not let in daylight upon magic. We must not bring the Queen into the combat of politics, or she will cease to be reverenced by all combatants; she will become one combatant among many.

In his eponymous play, probably written in 1596, Shakespeare has his principal character, Richard II, give a speech which included these lines:

‘Not all the water in the rough rude sea

Can wash the balm off from an anointed king.

The breath of worldly men cannot depose

The deputy elected by the Lord.’

But that, of course, is exactly what DOES happen in the play. While Richard is in Ireland the exiled Henry Bolingbroke lands in England and the result is that Richard is forced to relinquish the crown to the man who becomes Henry IV. The anointing balm can’t protect Richard from the lances of the rebels. Barmy to imagine anything else.

This lesson – that kings can be legitimately usurped - seems to have been what the mutinous Earl of Essex had in mind when, on the eve of his rebellion against the aged Elizabeth I in February 1601 he commissioned the Lord Chamberlain’s Men to perform Shakespeare’s play.

Just as men created God, so men created the monarchy. And if monarchists tended to forget this, the monarchy itself (with a few unfortunate exceptions) have understood it all too well. Charles I (much to the delight of my three-year-old grand-daughter) had his head chopped off, Charles II was brought back by the army, not by the Lord and his brother James II was deposed by the establishment and simply replaced by his daughter and her Dutch husband.

When that bloodline looked like running out (poor old Anne) it was parliament, not God, that alighted upon the little-known Sophia, from Germany, described in the Act of Settlement (1701) as “the most excellent princess … electress and duchess-dowager of Hanover”.

The family from which future British monarchs would spring in perpetuity would be hers, “the heirs of her body, being Protestant”. The acquiescence of the Scots – who were not yet part of the United Kingdom – to this agreement was bought with commercial concessions to Scottish traders. The Almighty was not involved, and – whatever the Hallowe’en flummery of a coronation - legitimacy derived not from the magic of a bloodline, but from the decision of a purely temporal and often unsentimental authority. You would have to be a fool of a monarch or prospective monarch not to realise this and behave accordingly. And so, with greater or lesser success, the royal family has tried to be thing that the people or their representatives want it to be.

Most successfully in recent years that thing has been the Pageant Family - mum, dad, kids, grannie, dogs, ponies, blazing fires – the suburban ideal except translated into a fairy tale setting. Exemplary, relatable lives lived out in a splendour which - until Donald Trump – even an American president couldn’t match.

In a steady state our Oedipal rebellion is kept in check by the powerlessness and lofty neutrality of our head of state, our stupidity is mollified by the diverting spectacle of royal events, our rebels are co-opted into the establishment: arise Sir David Hare, Sir Patrick Stewart, Dame Emma Thompson and many others.

Beyond the political fray the family monarch is able to reward us, embody our best behaviours, to unite us when others seek our division. These are no small things. In December 2019 – thanks I think to the mischievous historian Simon Sebag Montefiore – I made my one and only trip to Buckingham Palace to hear Prince Charles make a perfectly crafted and reassuring speech to the Jewish communities who were feeling a bit raw because of events in the Corbyn Labour party.

“It can’t be good for people to lead vicarious lives, made up partly of prurience and partly of deference, and fixated on the doings of an undistinguished and spoiled family.”

The very far from last words of Christopher Hitchens, commoner

The cultural cringe

For all that, as “subjects” we pay a price that Ernest Jones missed altogether. We can never be equal to the royal family, we must always be inferior; our lives are always somehow less than theirs, not because of merit, but because of birth. This is turn creates a hierarchy of social values and the habit of bowing before unearned privilege.

One very visible aspect of this is what the former Australian prime minister Paul Keating called a “cultural cringe”, in this case before the ideas of aristocracy and landed wealth. Displayed for us is the nexus of horse racing, polo, skiing in Klosters, holidays on Mustique, large houses, Ascot, huge estates, armies of servants, helicopters, limousines, public schools, and the ability to bestow honours on people for no other reason than they are friends of the family and usually also possessed of hereditary titles.