Pining for the slums

How one book became the Bible of false nostalgia

This piece first appeared on The Londoner site last month. The Londoner is a new venture, which is part of a wider UK enterprise by journalists to fill the void left by the decline in local newspapers. It includes long reads, investigations and reports from parts of the capital that tend not to get much coverage. You can find it here: https://www.the-londoner.co.uk/

PINING FOR THE SLUMS

We’re living through a moment of almost crippling intellectual pessimism here in Britain. On the right and on the left everything is better than here and any time is better than now. And one of the primary bits of collateral damage in this gloomy competition are our cities and especially London. They are places either of alienated anomie or of filth and criminality. One young Times writer recently explaining the appeal to his generation of going to live in Dubai conjured up a friend who had returned from an unspecified airport on a train where every single toilet had been vandalised, to an unspecified city station beside which crack addicts congregated.

In fact many Britons have always been attracted to go and work in sunnier or larger countries where houses are cheaper and taxes are lower. In the post war period those countries were Australia, South Africa and (though admittedly colder) Canada which, unlike the Emirates, also offered the two million permanent British migrants a fast track to equal citizenship. The Times writer might also care to examine what happens to Brits if they are thought by the Emiratis to have expressed the wrong views, as here:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cdd0ggyvd86o.

Right now there is a strongly held idea that migration represents only loss and loss above all loss of coherent community. This was the central proposition of the famous division proposed by the journalist-cum-thinktanker David Goodhart of the world between Somewheres (rooted, patriotic, community-minded, homogeneous) and Anywheres (mobile, cosmopolitan, individualistic, heterogenous).

An irony is that to a significant extent this imagined division was one imposed by middle class intellectuals on largely working class people. The middle classes of course were expected to be mobile – their children would leave home to go to university and never return, their careers would take them to whatever place or country demanded their skills. They would marry across borders; it is another irony just how often right-wing nationalist politicians - from Farage to Trump via Jenrick - will have chosen spouses from other countries

The middle classes would do all this in search of fulfilment. Working class communities on the other hand could only suffer from such dilution of “tight-knit” community. “We was poor, but we was happy and everyone looked out for everyone else” might be a distillation of this credo. Move people in or move people out and the result could only be loss.

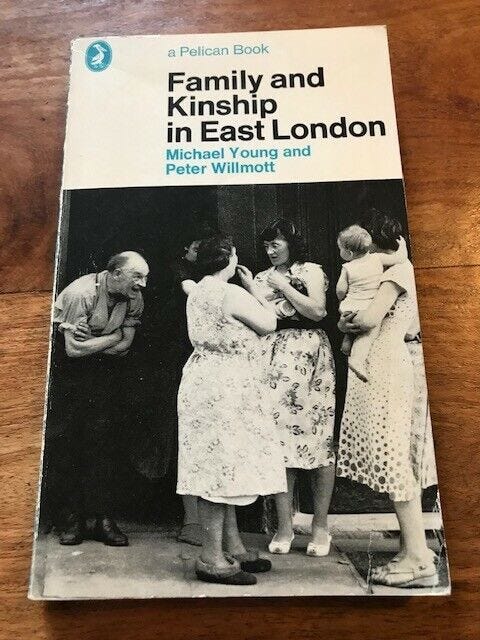

The work that above all gave intellectual heft to this notion was first published in 1957, sold half a million copies and has been described as “one of the influential sociological studies of the twentieth century”. The authors of Family and Kinship in East London were two centre left academics, Michael Young and Peter Wilmott. Young (later Baron Young of Dartington) was a considerable and tireless figure on the centre left, having drafted Labour’s manifesto of 1945 while serving as the party’s director of research and later becoming the first director of the Social Science Research Council.

In the mid 50s he and Wilmott undertook their study of the effects of “slum clearance” on the people coming from a small area of the East London borough of Bethnal Green. The book was largely based on interviews with those left behind and those who had moved to a new housing estate in Debden in Essex. In this period Bethnal Green, like the other inner London boroughs, lost up to two thirds of its population to external or internal migration.

Although the book is ostensibly a piece of neutral social science, there is an unmistakable tone of regret running through it. In Young and Wilmott’s Bethnal Green a woman can record encountering 14 known and named people on a half hour shopping trip to the end of her road – people she can nod to or stop to talk with. In their Debden no such intimacy is possible.