When the British theatre director Mark Rosenblatt decided to finally write a long-considered play about Roald Dahl’s antisemitism, he could hardly have imagined that it would open in such horribly resonating circumstances.

Back in 1983 what propelled Dahl to write the book review that publicly revealed his attitude to Jews, was the Israeli invasion of Lebanon a year earlier. Published in the magazine Literary Review Dahl’s piece began:

In June 1941 I happened to be in, of all places, Palestine, flying with the RAF against the Vichy French and the Nazis. Hitler happened to be in Germany and the gas-chambers were being built and the mass slaughter of the Jews was beginning. Our hearts bled for the Jewish men, women and children, and we hated the Germans. Exactly forty-one years later, in June 1982, the Israeli forces were streaming northwards out of what used to be Palestine into Lebanon, and the mass slaughter of the inhabitants began. Our hearts bled for the Lebanese and Palestinian men, women and children, and we all started hating the Israelis.

Dahl did not concern himself with why the Israelis had taken such a drastic step – which was to expel the armed Palestinian groups which had taken up residence in Southern Lebanon after having been expelled from Jordan a decade earlier. The book he reviewed was a powerful collection of photographs and prose about the horrible human consequences of that war, not an account of it.

However Dahl’s piece rapidly departed from being about the book and became about something else. “Never before in the history of man”, he wrote:

…has a race of people switched so rapidly from being much-pitied victims to barbarous murderers. Never before has a race of people generated so much sympathy around the world and then, in the space of a lifetime, succeeded in turning that sympathy into hatred and revulsion.

This relentless confidence both in his own sweeping judgement (“never before in the history of man”) and in its being universally shared (“around the world”) led Dahl to the kind of concluding peroration that many Jews fear is the inevitable end point of such an argument. “Every Jew in the world should read” the book, he wrote, because:

Now is the time for the Jews of the world to become anti-Israeli. But do they have the conscience? And do they I wonder have the guts? Or must Israel, like Germany be brought to its knees before she learns how to behave in the world?

Even a stinker like Hitler

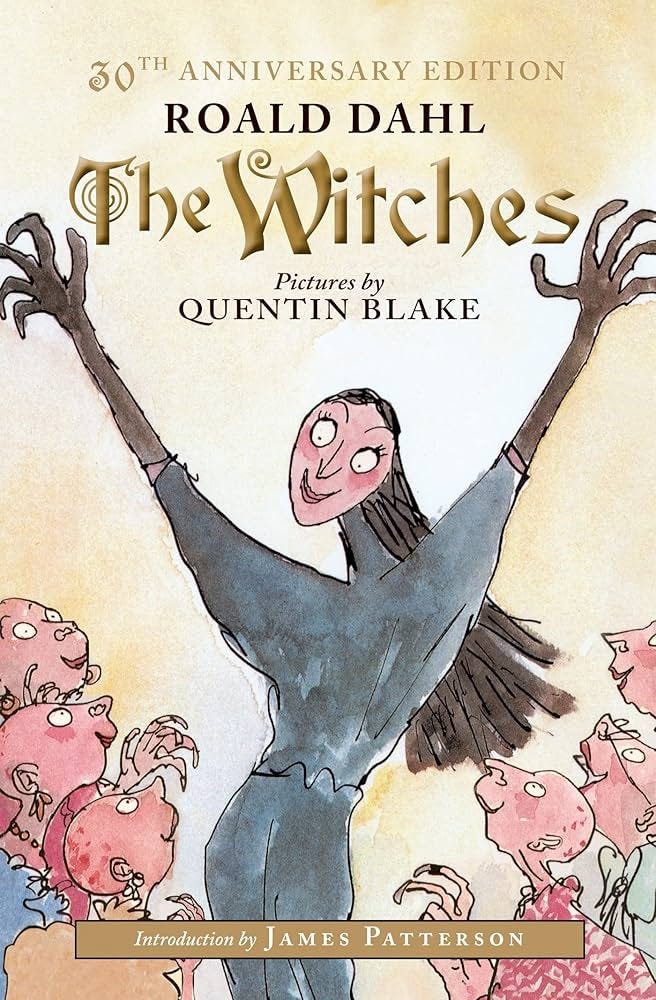

Rosenblatt’s play opens with Dahl considering the artwork for his new book The Witches and expecting a visit from a representative of his American publishers, who want him to apologise for what he had said. His resistance to such a withdrawal and his arguments with the other characters – two of them Jewish – form the (fictional) meat of the drama.

And here I need to alert you to a spoiler - though what happens next is a matter of record. In an act of defiance Dahl agrees to a telephone interview with a young journalist from the New Statesman. And tells him that:

There is a trait in the Jewish character that does provoke animosity. Maybe it’s a kind of lack of generosity towards non-Jews. There is simply a sense of tribal closeness, you know, sticking together. You know they killed 22,000 civilians when they bombed Beirut last year?

A sense perhaps their pain is the only pain worth mentioning. When it comes to Israel's appalling behaviour, I believe you see it all too clearly- in Israel's powerful influence over the US treasury, if we must be frank. Over the presidency. At any and all costs. Except its own.

The US treasury! And as if Dahl hasn’t hit almost all the stereotypes deployed by antisemites over the years, he has that one last crushing observation:

There’s always a reason why anti-anything crops up anywhere. Even a stinker like Hitler didn’t just pick on them for no reasons.

Full exegesis

The backwash from this exercise in partly blaming the Jews for their own mass extermination was minimal. The Witches sold well, it became a play and then a film and then an opera and then another film, its main villain appeared on a commemorative stamp, and its earnings filled the coffers of the Dahl estate. His publishers stood by him.

However Dahl himself believed that the row over his review and his subsequent statements had cost him a knighthood. In 1990, not long before he died he gave an interview to The Independent in which he claimed that the Israeli invasion of Lebanon had been “hushed up” by newspapers “because they are primarily Jewish-owned”. Which would have been a revelation to Rupert Murdoch and the Rothermeres - who perhaps he confused with the Rothschilds. Dahl went on:

I’m certainly anti-Israeli and I’ve become anti-Semitic in as much as that you get a Jewish person in another country like England strongly supporting Zionism. I think they should see both sides. It’s the same old thing: we all know about Jews and the rest of it. There aren’t any non-Jewish publishers anywhere, they control the media—jolly clever thing to do—that’s why the president of the United States has to sell all this stuff to Israel.

You might call this the Dahl exegesis – the gradual extrapolation out of one opinion (that Israel is behaving badly on its borders) to a contempt and hatred for the Jews as a people. It’s the journey that many Jews think they see many embarking upon right now.